The Tobacco Pipes of Great Historical Figures: Who Smoked Them and Why

The tobacco pipe has accompanied human history for centuries, crossing eras and cultures, and undergoing numerous evolutions since its first appearance.

Today it no longer enjoys the popularity it once did, but it has bequeathed us a rich repertoire of illustrious figures who have made it an inseparable companion.

Some figures, such as Albert Einstein, are now inextricably linked to the image of the tobacco pipe.

In this article we will explore the link between great historical figures and slow smoking, immersing ourselves in their passion and discovering how they lived this intimate and fascinating ritual.

Introduction: The tobacco pipe as a symbol of style and character

With the passage of time, the tobacco pipe has become a true status symbol, and this has prompted many smokers today to be inspired by the great figures of the past, finding in the act of smoking not only the pleasure of tobacco tasting, but also character and style.

It is not uncommon to come across historical photographs depicting famous figures while smoking a tobacco pipe: images that have helped solidify, in the collective imagination, the association between the tobacco pipe and the thoughtful, educated and responsible man.

Why was the tobacco pipe loved by great historical personages?

For centuries, up to the 1940s, the tobacco pipe was the main tool for smoking tobacco, so much so that it was common to find at least one in every home.

The cigar also enjoyed great popularity, albeit to a lesser extent than the tobacco pipe.

Indeed, there is no shortage of period images and accounts of historical figures intent on smoking cigars, a sign that both modes of tobacco smoking coexisted at the time, each with its own appeal.

The appeal of the tobacco pipe over the centuries

Over the centuries, the tobacco pipe has gone through a significant evolution: from the French meerschaum, which was widespread in the 18th century, to the briar, which in the 19th century consecrated its role as the main tool for tobacco consumption.

Today the tobacco pipe is experiencing a new phase: although it is no longer a widely consumed object, it is enjoying growing interest among enthusiasts, who are rediscovering it as a collector's item, a symbol of style and status, and an authentic example of craftsmanship.

It is now a niche passion, very different from the mass circulation of the past, but one that is generating renewed fascination around the world of slow smoking.

The tobacco pipe as a symbol of intellectuality, power and reflection

The tobacco pipe, because of the slow and reflective experience it offers, has always been associated with intellectuality and, in certain contexts, even power.

Numerous period photographs depicting intellectuals and authority figures while smoking a tobacco pipe have stuck in the collective imagination, reinforcing this association.

When one thinks of the great tobacco pipe smokers of the past, names like Albert Einstein or J.R.R. Tolkien immediately come to mind: prominent personalities who embodied culture, depth and authority. And so, over time, the tobacco pipe also ended up inheriting these same values, becoming a symbol of intelligence, prestige and thoughtfulness.

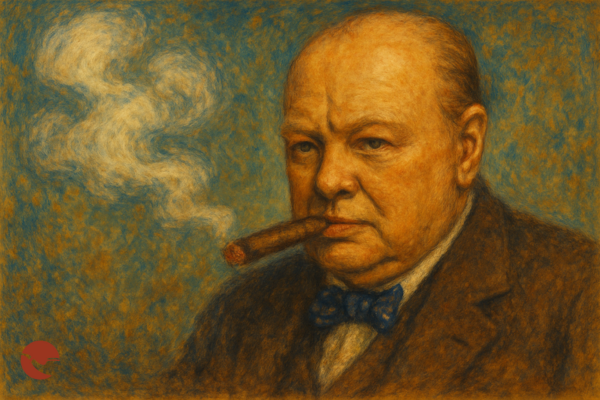

Winston Churchill and the tobacco pipe: an icon of the 20th century

Let's dispel a myth right away: Winston Churchill was yes a famous smoker, but not a tobacco pipe smoker-his real love was the cigar.

When talking about famous smokers, his name is among the first to come to mind. Not surprisingly, there are countless photographs of him with a cigar between his teeth, an element that became an integral part of his public image and unmistakable style.

It is said that wherever he went, Churchill left a trail of cigar smoke and ash, a detail that did not go unnoticed, especially among airline stewardesses of the time.

Tobacco pipe or cigar? Churchill's habits

Winston Churchill was one of the most celebrated cigar smokers in history, so much so that he deserved a vitola dedicated to him.

Churchill considered smoking an invaluable ally in dealing with the challenges of his busy political and personal life, believing that it helped him calm his nerves and maintain control in the most delicate moments.

While for many people smoking is just a harmful vice, for him it represented a tool for balance. In his collection of essays Thoughts and Adventures (1932), he wrote that without tobacco he would not have had the right temperament at crucial moments, nor would he have been able to contain his impulsiveness.

And in the end, despite his unhealthy habits, Churchill lived to be 90.

The link between the British leader and smoking

Those who had the opportunity to work or spend much time alongside Winston Churchill could testify to how deep the bond between the former British prime minister and the cigar was.

It is said, for example, that his wife had made him a kind of bib to wear in bed, to protect his pajamas from holes caused by the ash that fell as he smoked.

Also famous is the anecdote of the oxygen mask specially modified to allow him to smoke even during high-altitude flights during World War II.

But how was this enduring passion born?

It all began in Cuba, in 1895, when a young Churchill, then a military man, went there to observe the war of independence against the Spanish empire.

In the company of his colleague Reginald Barnes, he stayed for some time in a hotel where he discovered two local pleasures: oranges and, above all, cigars.

It was love at first sight, so much so that when he returned home he brought with him not only memories and impressions, but a new habit that was destined to last a lifetime.

He came to smoke between 8 and 10 cigars a day. He regularly received supplies directly from Havana, from friends and dealers, even during times of war, always ensuring a supply of fine cigars.

It is difficult to estimate how much he spent on cigars, but it is reported that one of his assistants noted how, in just two days, Churchill managed to smoke the equivalent of his weekly salary.

He even went so far as to build a personal cigar warehouse adjacent to his Kent estate, Chartwell Manor: a private collection of 3,000-4,000 cigars, all meticulously organized and catalogued.

From his first Cuban trip onward, Churchill was loyal to Havana cigars, particularly the Romeo y Julieta and La Aroma de Cuba brands. Both, in tribute to their most famous admirer, introduced a vitola bearing his name: the “Churchill.”

His way of smoking was also unique. Instead of cutting the cigar, he preferred to pierce its head with the end of a match. In addition, he invented the so-called bellybando, a strip of paper attached with a drop of glue around the cigar, designed to prevent the head from getting wet and flaking, especially since Churchill used to chew his cigars.

This expedient, in addition to enhancing the experience, also reduced the direct absorption of nicotine, allowing him to smoke more cigars throughout the day.

Churchill approached everything with absolute dedication: whether it was leading a nation through a world war or enjoying a cigar, he always did so with an uncommon passion and focus.

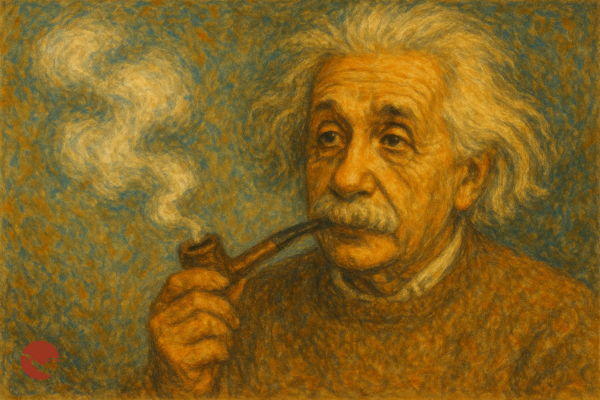

Albert Einstein: the tobacco pipe as a tool for reflection

Albert Einstein was a great enthusiast of the tobacco pipe, to the point that he is said to have drawn inspiration from this very slow and reflective ritual to develop some of his most revolutionary theories.

As evidence of the deep connection between the scientist and his tobacco pipe, one of Einstein's few remaining personal possessions is one of his tobacco pipes, now housed at the Smithsonian Institution, one of the world's most celebrated museums. Interestingly, it is also the most popular item in the entire collection dedicated to the physicist.

Einstein was not attached to material goods, but the tobacco pipe represented something different for him, almost a tool of thought. Not surprisingly, one of his most famous phrases reads, “I believe that tobacco pipe smoking contributes to a somewhat calm and objective judgment in all human affairs.”

Even when doctors advised him to quit smoking, Einstein could not entirely part with his inseparable companion. Quit yes, but only partially: in fact, he continued to carry it in his mouth, even empty, and chew it as if it were an indispensable presence.

The tobacco pipe on display at the Smithsonian, in fact, shows clear signs of chewing, confirming this curious habit.

Einstein and his love of the tobacco pipe

There is a curious anecdote that tells much about the connection between Einstein and his tobacco pipe: the story goes that he once accidentally fell off a boat and was once pulled aboard still with his tobacco pipe firmly clutched in his hand.

His love of the tobacco pipe, much like his love of sailing, stemmed from a deep desire for solitude and reflection, away from the distractions of the world.

Einstein was a lifelong member of the Montreal Pipe Smokers Club and is said to have been a great admirer of Revelation tobacco, an American blend produced by Philip Morris. He loved this tobacco for its aromatic complexity, a blend of Burley, Kentucky, Latakia, Perique and Virginia, capable of providing a rich and stimulating experience, much like his musings.

Why Einstein believed that the tobacco pipe aided scientific thinking

According to Einstein's own statements, the tobacco pipe played anything but a minor role in the formulation of his theories.

What really fascinated him, however, was not just the object itself, but the whole ritual that revolved around it: the choice of the shape, the right tobacco, the careful loading, and finally the first draw, experienced in silent contemplation. It was in those moments that his mind could roam free, away from the pressures of the world.

The tobacco pipes owned by the most famous physicist in history

Actually, not many details are known about the tobacco pipes that belonged to Albert Einstein, partly because few of his personal items have survived the passage of time. The scientist himself tended to get rid of them, placing no particular value on material possessions.

One of his tobacco pipes, however, was saved and is now housed at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington. It survived because Einstein gave it to Gina Plunguian, a friend and collaborator, a sculptor who made a bust in his honor. In gratitude, Einstein gave her one of his tobacco pipes, thus making it a precious object, not only because of its rarity, but because of the intimate connection it reveals.

It is a modest briar tobacco pipe, dating from 1948: about six inches long, with a stove barely an inch and a half across. It is the most popular piece in the collection dedicated to the scientist, precisely because it humanizes a figure often perceived as distant, and shows how deep was the bond between Einstein and his tobacco pipe, a simple object but essential to his inner balance.

Another famous tobacco pipe that belonged to the scientist is a 1940s Davidoff, of Billiard shape with a squared-off blowtobacco pipe, dating from around 1945. This specimen was sold at auction by Christie's in 2017 for £52,500, confirming the symbolic and sentimental value that Einstein's tobacco pipes continue to have today.

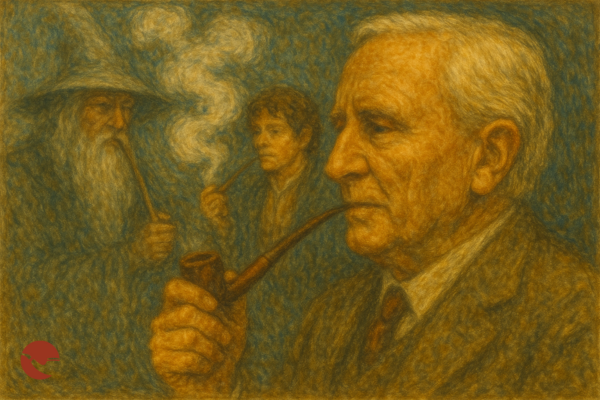

J.R.R. Tolkien and the tobacco pipe: inspiration for the world of Lord of the Rings

J.R.R. Tolkien left a deep imprint not only on literature, particularly fantasy literature, but also on the world of the tobacco pipe.

He was a great smoker and, as a true enthusiast, he also wanted to transmit this passion to his characters, who often indulge in long smokes in moments of reflection or conviviality.

In his works, the tobacco pipe is not just a scenic detail, but a symbolic object, rich in meaning. Already in The Hobbit, and even more so in The Lord of the Rings, the tobacco pipe is an integral part of the hobbits' daily life: a ritual of calm, friendship and wisdom.

The role of the tobacco pipe in Tolkien's life

J.R.R. Tolkien was a great tobacco pipe smoker, and his passion for slow smoking seems to have its roots in childhood. It is said that it was Father Francis Morgan, the figure who raised him after he was orphaned at only 12 years old, who introduced him to this world.

Father Morgan was in the habit of smoking a long cherry wood tobacco pipe, and that quiet, meditative gesture struck young Tolkien deeply, so much so that he urged him to try it himself. It was the beginning of a habit that would accompany him throughout his life.

Even as a professor, the tobacco pipe never left him. His students recounted how difficult it was to understand him during lectures, complicit in a slight speech defect aggravated by the fact that he often held his tobacco pipe in his mouth while he spoke.

As for tobacco, Tolkien was known to smoke Capstan Navy Cut, an English blend popular at the time. Several cans of Capstan used for storing small items were found in his house, and an invoice dated 1972 confirms the purchase of a pound of this blend. His son Christopher, before he quit, also smoked the same tobacco.

It was rare to see Tolkien without a tobacco pipe between his lips. Those who hung out with him say that, during conversations, he used to stroll back and forth, lighting matches one after another in an attempt to relight his tobacco pipe.

In a 1966 interview, he declared with his typical humor, “Every morning I get up thinking, ‘Well, another 24 hours of smoking.’”

The tobacco pipe in Tolkien's novels: between fact and fiction

In the universe created by J.R.R. Tolkien, the tobacco pipe is not just a prop: it is a recurring symbol, deeply connected to the life, culture and values of hobbits.

Already in The Hobbit, the prequel to The Lord of the Rings, the tobacco pipe appears from the very first pages: Bilbo Baggins is described smoking a long wooden tobacco pipe, so long that it almost reaches his feet. And even at the end of his adventure, the tobacco pipe is still there: Bilbo and Gandalf relax together, with Bilbo handing him a jar of tobacco, as if to seal a return to normalcy and quiet after the turbulence of the journey.

In Lord of the Rings, the tobacco pipe plays an even more symbolic role. It is at the moment when Bilbo, lost in Gollum's caves, accidentally finds the Ring on the floor that he realizes he has also misplaced his tobacco pipe. This seemingly minor detail highlights a profound contrast: on the one hand the dark attraction of absolute power, on the other the simple and genuine desire for a pause, a moment of reflection and peace. In that instant, the tobacco pipe seems to represent a force opposite and silent to the Ring of Power.

Tolkien, who himself passionately smoked a tobacco pipe, transferred this symbolism directly into the plot and moral of his work. The tobacco pipe thus becomes an emblem of the Hobbit way of life: humble, serene, authentic. While the more powerful beings of Middle-earth pursue dominance and control, it is Bilbo who finds the Ring and, instead of being corrupted by it, returns home, seeks his tobacco pipe and takes refuge in simplicity.

Tobacco itself occupies a place of honor in the saga: Tolkien devotes the entire second chapter of the prologue of The Fellowship of the Ring to it. In this passage, rich in detail, the writer recounts the origin of the “pipe-weed” in the Shire, even proposing several theories about its spread. Merry, one of the main characters, is described as a true tobacco expert, almost a tobacconist in Middle-earth.

All this is not coincidental. Tolkien includes such a meticulous explanation of slow smoking because for the hobbits the tobacco pipe is much more than an accessory: it is a ritual of friendship, introspection and peace, ever present in the quieter, more human moments of the narrative.

The tobacco pipes of the characters in “The Lord of the Rings”

In Tolkien's world, the tobacco pipe is also a symbol of friendship and personal bonding. This is illustrated, for example, by Bilbo's gesture of giving Merry and Pippin two elven tobacco pipes with pearl mouthpieces, tied by a silver true: a precious gift that goes far beyond material value.

Another emblematic episode concerns Gimli, who had lost his tobacco pipe in Moria. In a rare moment of peace and refreshment, Pippin offers him one of the two tobacco pipes he was carrying, as if they were sacred objects. He recounts that he carried it with him throughout the journey, not really knowing why; after all, they believed that the Shire was the only place where pipe-weed was grown. Only then does he finally understand its meaning: to give it to a friend at the right time.

Even the corrupt wizard Saruman is touched by the charm of the tobacco pipe, although he initially despises it. In one scene, he shows himself annoyed by Gandalf's smoking, accusing him of playing with his “toys of fire and smoke” even during important discussions. Gandalf, with his usual wisdom, replies to him that tobacco pipe smoke blows shadows away from the mind.

Despite his dismissive words, Saruman was secretly fascinated by it: so much so that he secretly organized the export of tobacco from the Shire. This detail is revealed by Merry and Pippin, who after the wizard's defeat find jars of tobacco stored in his warehouses.

Also in these episodes, Tolkien shows us that the tobacco pipe is not just a narrative accessory, but a profound symbol of peace, sincere bonds, and humanity, as opposed to greed and power that corrupts.

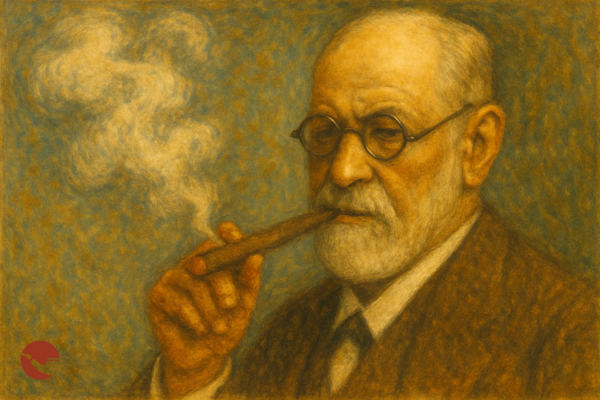

Sigmund Freud: the tobacco pipe and the world of psychoanalysis

“Smoking is one of life's greatest and cheapest pleasures; if you decide in advance not to smoke, I can only feel sorry for you.”

With these words, Sigmund Freud addressed his 17-year-old nephew Harry, who had refused a cigar offered to him by his uncle.

Freud was not a tobacco pipe smoker, but rather an avid cigar smoker-he was said to smoke up to twenty a day. Smoking, for him, was an integral part of thinking, working and, ultimately, of life itself.

A ritual that accompanied him for most of his life, despite serious health consequences.

Freud and the ritual of smoking

Sigmund Freud began smoking cigars at age 24, influenced by his father, who was also a smoker until his death.

In his case, it was clearly an addiction rather than a habit, considering the impressive amount of cigars he consumed each day.

For Freud, the cigar represented more than just pleasure. He called it “a protection and a weapon in the fight of life for 50 years”, as he confided to a friend.

He was convinced that smoking helped him concentrate, enhance thinking and maintain self-control.

Not surprisingly, then, there was always an ashtray on his desk, carefully placed to his right, within easy reach.

In 1923 he was diagnosed with mouth cancer, and over the next sixteen years he underwent more than 30 surgeries. Despite the pain, the difficulty in speaking, and the discomfort in feeding himself, Freud never completely gave up his cigars.

His connection with smoking was so deep that, even at the point of death, he talked about it: aware that he could no longer smoke them, he asked his brother to take care of his cigar stash. It was a gesture that said much more than words could: that pleasure, now denied, remained for him one of the most intimate symbols of his own identity.

The symbolic significance of smoking in psychoanalysis

For Freud, slow smoking was also a profound source of psychic pleasure, in line with many of his psychoanalytic theories.

Indeed, he was convinced that gestures such as smoking, kissing or thumb sucking all derived from an unconscious desire to repeat life's first sensual experience: the sucking of an infant.

Cigar smoking, in this perspective, was not just a habit, but a way to gratify a primary need, related to the oral phase of growing, which Freud believed would continue to influence behavior into adulthood.

Mark Twain: the tobacco pipe of a great writer

Mark Twain, referred to by his niece Jean Webster as “the human furnace” and “the smokiest man in the world,” was undoubtedly one of the most inveterate smokers in history, as well as one of the most influential authors in American literature.

Famous for his wit and provocative spirit, Twain smoked almost compulsively, to the point of buying whole barrels of cigars and cob tobacco pipes in bulk.

“I smoke all the time, that is, all the time”, so he wryly stated.

His historical friend, William Dean Howells, once declared, “I don't know how much a man can smoke and live, but apparently he smoked as much as a man could, because he smoked incessantly.”

His passion for smoking was born very early: at only 7 years old, probably influenced by the environment in which he grew up, the small town of Hannibal, Missouri, which was home to a tobacco factory.

His family, however, did not approve of this habit and tried for a long time to get him to quit, even in adulthood.

Before he married Olivia Langdon, his future in-laws tried to convince him to give up both smoking and alcohol. Twain made an attempt, imposing on himself a limit of only one cigar a day. But he soon circumvented the constraint: he began to seek out larger and larger cigars, capable of lasting hours, and eventually returned to his habits without too much guilt.

One of his most iconic phrases about smoking reads, “As an example to others, and not that I value moderation, it has always been my rule never to smoke when I am asleep, and never to abstain when I am awake.”

Twain went so far as to smoke up to 30 cigars a day, often alternating with his tobacco pipe. Only in old age did he limit himself, in a manner of speaking, to four cigars a day.

For him, slow smoking was an integral part of life, writing and his own identity.

The tobacco pipe as a companion to writing and inspiration

Mark Twain was convinced that smoking was an integral part of the creative process. Writing without a tobacco pipe or cigar between his fingers seemed unthinkable to him. In all likelihood, without tobacco we would never have any of his bestsellers.

During the writing of The Innocents Abroad, while on tour, he was visited in his hotel by an anonymous journalist from The New York Evening Post, who had the opportunity to observe his working method up close.

The journalist described a chaotic, smoke-soaked scene: the bed unmade for weeks, the room neglected, tobacco scattered everywhere and a dozen tobacco pipes scattered throughout the room, even in the bathroom.

The air was so thick with smoke that, according to the reporter, the flies died instantly. He marveled at how Twain managed to survive in that atmosphere, but described it as he paced back and forth, cursing and smoking incessantly for hours.

Even the family's attempts could not stop him. His father-in-law Jervis Langdon tried to convince him to quit by offering him $10,000 (the equivalent of about $187,000 today). Twain, with his usual wry wit, agreed only in part, promising to abstain on Sunday afternoons. But upon his father-in-law's death, he returned to his habits without any more qualms.

It was from that very moment that Twain began to live by his own rules, abandoning all attempts to conform to the expectations of others.

He thus began a new phase in his career, devoting himself fully to writing novels and achieving worldwide fame with the success of Roughing It.

Twain's writings on tobacco pipes and smoking

The tobacco pipe and tobacco were not only a constant in Mark Twain's personal life, but also became recurring elements in his literary works, often with direct implications for the plot, characters and themes covered.

Smoking appears in such famous novels as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Roughing It, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court and many others, helping to delineate atmospheres, characters, and situations.

In A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, for example, Twain tells the story of an industrial foreman catapulted back in time to the court of the legendary ruler. In several scenes, the protagonist also lights his tobacco pipe in armor, puffing smoke from his helmet, resulting in comic and surreal moments that contrast modernity with the ancient world of chivalry.

Tobacco also often takes a central role in short stories. Such is the case with Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut, an ironic narrative in which the protagonist is tormented by a deformed caricature of himself, an embodiment of his conscience, which continually nags him on the subject of tobacco.

Only through the words of a close relative is he able to rid himself of it, in a brilliant parody of inner conflict and Victorian morality.

Through these examples, Twain not only depicts smoking as a habit or personal tic, but elevates it to a narrative tool, often symbolic, capable of representing rebellion, reflection or simple humanity.

Which tobacco pipes did Mark Twain prefer?

In the 1960s, Mark Twain's daughter Clara donated a Peterson pipe that had belonged to her father to the Mark Twain Museum in Hannibal, the town where the author rests.

The tobacco pipe, far from being in pristine condition, has a noticeable burn all over the rim and marked signs of wear and tear. Twain, in fact, was not known for caring for objects: he did not perform any regular maintenance, treating his tobacco pipes with the same rough and casual spirit that characterized him.

In 1980, the Peterson company made an exciting discovery: an old photograph of Twain smoking what looked like a Peterson System. Careful analysis of the silver true revealed that it was a model dating back to 1896.

Probably Twain, during one of his many trips, learned of Peterson's patented system and decided to try it out, adding a specimen to his collection.

The discovery prompted Peterson to put that specific model, long discontinued, back into production. The result was the birth of the Mark Twain series in 1980, with an initial production run of 400 numbered models, followed by a second run of 1,000 in 1981. From 1983, numbering was abandoned, except for a limited gold edition in 1985. Some models with real 1998 hallmarks indicate that production continued in later years.

Mark Twain pipes were large, with a Full Bent shape, equipped with a tapered palatal mouthpiece (P-Lip system) and a finely punched silver true.

Available in smooth, sandblasted and rusticated finishes, they can be compared in features and quality to today's Peterson Deluxe System. According to enthusiasts, these tobacco pipes offered excellent draught and particularly excellent performance with Virginia and Flake tobaccos, which made them highly valued for both collecting and everyday smoking.

CLICK HERE FOR DELUXE SYSTEM PIPES

Bertrand Russell: the tobacco pipe and philosophy

“I smoke a tobacco pipe all day long, except when I eat or sleep.”

So declared, with his typical humor, Bertrand Russell in an interview at age 90, surprising everyone in saying that 70 years of tobacco pipe smoking had never caused him any health problems.

Russell had started smoking at age 20 and never stopped. For him, the tobacco pipe was more than a habit: it was a companion in his thinking, a means to accompany the long philosophical and political reflections that marked his life.

In the same interview, he told a curious and grotesque anecdote: he survived a plane crash only because he had insisted on sitting in the smoking area. All the passengers who had chosen the non-smoking section lost their lives, while he was saved. Russell, with cutting irony, attributed his salvation precisely to smoking a tobacco pipe.

Russell and the tobacco pipe as an emblem of rational thought

Bertrand Russell's emotional life was anything but simple. Orphaned as a child and scarred by his father's depression, he lived with a constant shadow that accompanied him into adulthood.

Russell deeply feared madness and often spoke of feeling pursued by it. His vanity, as he himself admitted, did not help him: he had little faith in the human race and believed that the only way to lead a truly happy existence was to cultivate broad interests so as not to succumb to the burden of the mind.

In this constant search for balance, the tobacco pipe and tobacco were a valuable anchor for him. Not only did they comfort him in difficult times, but they also seemed to help him in his moments of insight, contributing to the philosophical and social views that still influence our modern thinking.

The philosopher and his view of smoking

Bertrand Russell remembered with extraordinary accuracy not only the day he began smoking a tobacco pipe, but even the exact moment.

In an account that has remained famous, he described a walk in 1894 along Trinity Lane in Cambridge. He had gone out that day to buy a tin of tobacco. As he was walking back, something struck him like lightning: a dazzling insight into the ontological argument for God's existence.

In excitement, he threw the newly purchased tin into the air, and as he caught it in the air, he exclaimed:

“Great Scott, the ontological argument is valid!”

This episode not only testifies to the closeness between the act of smoking and intellectual activity in Russell, but confirms how much the tobacco pipe was an integral part of thought itself for him: a catalyst for insights as complex as they were memorable.

The tobacco pipes used by Russell and his public image

Russell often mentions his tobacco pipes in his autobiography, although he never identifies the brand. Photographs depict him mostly with classic straight tobacco pipes, similar in size to a Group 3, but there are also pictures in which he smokes curved tobacco pipes, very similar to the Peterson 69 P-Lip.

He liked to carry at least two tobacco pipes with him, one in each pocket, alternating them to ensure that each one had had enough time to rest and be fresher when smoked, a sign of the care and attention he paid to the ritual.

On the tobacco he favored, however, we have more certainty. As stated by biographer Alan Wood, Russell regularly ordered a quarter-pound tin a week of Fribourg & Treyer's Golden Mixture, a fine, well-balanced blend.

He lived to be 97 years old and smoked the tobacco pipe to the end of his days, never feeling the need to reduce his consumption.

Other great tobacco pipe smokers in history

In addition to the historical tobacco pipe smokers we have described so far, there are other iconic figures who, although they have not left in-depth accounts of their relationship with the tobacco pipe, are often associated with the instrument through images and stories.

Prominent among them are Orson Welles and Pablo Picasso, two brilliant and complex personalities who, as we shall see below, shared a pleasure in slow smoking, albeit in a more discreet or less well-documented way than other protagonists in history.

Orson Welles and the link between cinema and the tobacco pipe

Orson Welles, film and theater genius, was also an avid smoker. At a young age he was often portrayed with a tobacco pipe, but it seems that beginning in the 1950s he abandoned slow smoking in favor of cigars, which became his hallmark.

Among his favorite brands are said to have been Montecristos and Por Larrañaga. According to the famous Zino Davidoff, Welles always asked to open the cigar box before buying, although he still ended up buying it even if he refused.

His love for cigars was not limited to his private life: he played several cigar-smoking characters on the big screen, reinforcing the association between his face and that iconic gesture.

One particularly curious episode involves a gift from Ernest Hemingway, who, learning of his love of cigars, gave him a cigar ashtray, which became one of Welles' most cherished objects.

But it was this passion that also generated tensions in his private life. As recounted in the book The Cigar That Fell in Love With a Tobacco pipe by David Camus and Nic Abadzis, his ex-wife Rita Hayworth was annoyed by the constant presence of cigars in the house.

One day, exasperated, she decided to smoke one of the cigars carefully kept in Welles' humidor, unaware that it was a one-of-a-kind, rolled by a famous torcedor now gone.

Legend has it that Welles, furious at the loss, decided to divorce Hayworth, marking the end of their marriage.

Clarence Darrow: the tobacco pipe in American courts.

Clarence Darrow was probably the most famous defense lawyer in the United States in the last century, known for his magnetic eloquence and ability to argue unpopular cases with memorable harangues.

Although not a tobacco pipe smoker, Darrow is remembered for a curious cigar-related technique called “cigar-ash.”

According to the account, Darrow allegedly used this technique to distract the jury during the prosecution's arguments by allowing the ash from his cigar to grow in length without falling, thus attracting attention. At that time, in fact, smoking was allowed inside courtrooms.

The trick, it is said, was to insert a straightened paper clip or piano wire inside the cigar to strengthen the ash and prevent it from breaking.

However, there is no official confirmation that Darrow ever actually used this ploy: neither in his autobiography nor in the accounts of H.L. Mencken, the journalist who closely followed the famous Scopes Trial.

It is therefore possible that this is more of a fascinating legend than an actual fact.

However, this technique was revived and experimented with in the 1980s, as reported by an American legal magazine, which claimed it had been used in a hearing in Dallas, thus reviving the “cigar-ash” myth in the courts.

Pablo Picasso and the aesthetics of the tobacco pipe

The famous painter Pablo Picasso is not remembered as a regular tobacco pipe smoker. In fact, most photographs and accounts related to him depict him with cigars or cigarettes, rather than a tobacco pipe.

There are, however, a few rare images in which he appears intent on smoking a tobacco pipe, but these are isolated incidents, not part of his daily habit.

What is extremely significant, however, is the role of the tobacco pipe in one of his most famous works, “Boy with a Pipe”, painted in 1905 during his Rose Period.

The work depicts a young boy holding a tobacco pipe in his left hand, in an atmosphere suspended between innocence and maturity. This painting became famous not only for its artistic value, but also for its economic value: sold at auction by Sotheby's in 2004 for about $104 million, it set a world record at the time for a work of art sold at auction, a record held until the early 2010s.

Although the tobacco pipe was not a regular companion for Picasso, he found in it a powerful iconographic symbol, capable of enriching the narrative and symbolic depth of one of his most beloved works.

The tobacco pipe as status symbol and hallmark

In recent years, the tobacco pipe is experiencing a rediscovery as an object of style and distinction.

In an age when production has become more refined and artisanal than ever before, the tobacco pipe takes on a far different value than in the days of its heyday. Today, each piece can be considered a small work of art, crafted with care and attention to detail.

This renewed appreciation, combined with strong symbolic ties to historical figures of great charisma and intellect, has brought the tobacco pipe back to the center of interest for many smokers, not only as a tool for slow smoking, but also as an emblem of personality, reflection and timeless style.

Why is the tobacco pipe often associated with intellectuals and leaders?

The tobacco pipe has always been associated with intellectuals and leaders because of its association with the idea of reflection, calm and style.

In the collective imagination, many influential men of past centuries, particularly figures of power and authority, are often remembered in the act of smoking a tobacco pipe, even at crucial moments in their personal or political history.

The tobacco pipe, in these cases, was not just a smoking object, but a real mental support, a means of slowing down, thinking, pondering.

This is how, over time, the tobacco pipe became a symbol of decision-making, balance and introspection, qualities attributed as much to great thinkers as to those called upon to make difficult decisions.

For those who live by study, analysis and research, the tobacco pipe has often accompanied reasoning, becoming a silent but significant companion in the path of thought.

How the tobacco pipe helped create an iconic image of these characters

Until after World War II, the tobacco pipe was an object of everyday use, the main tool through which tobacco was smoked.

At a time when many iconic figures were also smokers, it is easy to find them in archival photographs intent on smoking a tobacco pipe, often in moments of reflection or decision.

Over time, this helped to build a special aura around such figures, depending not only on the prestigious roles they held or the feats they achieved, but also on the image of the tobacco pipe itself: an object that, as it fell out of common use, took on an almost symbolic value, representing intelligence, introspection and charisma.

The decline and return of tobacco pipe smoking among modern thinkers

Beginning in the 1940s, the tobacco pipe began a slow decline, marked mainly by the spread of cigarettes, which began to dominate the market.

In an increasingly fast-paced world marked by the postwar economic recovery and a disposable-oriented lifestyle, the cigarette became the means of tobacco consumption best suited to modern rhythms: fast, convenient and immediate.

Today, however, the world of smoking is also undergoing another transformation. Cigarettes, increasingly criticized for their harmfulness, are the focus of new restrictions and are often being replaced by electronic devices, which respond to new consumption needs and trends.

In parallel, however, there is an interesting phenomenon: the rediscovery of the tobacco pipe.

In an age dominated by speed and constant distraction, the slow, ritualistic and reflective experience of smoking a tobacco pipe presents itself as a form of endurance, an authentic break.

And precisely because it is so distant from the hectic pace of our days, the tobacco pipe is making a comeback, even among younger people, as a symbol of style, personality and self-discovery.

Conclusion: The tobacco pipe as a companion to extraordinary men

The tobacco pipe has accompanied man for centuries, and has also been a silent companion of numerous historical figures who have left their mark on history.

In this article, we run through the stories, trivia, and anecdotes related to the great tobacco pipe smokers of the past to find out everything there is to know about this fascinating connection.

Summary of the great tobacco pipe smokers in history

Among the most famous tobacco pipe smokers in history are such names as Albert Einstein, J.R.R. Tolkien, Mark Twain, and Bertrand Russell. All of them were inveterate smokers, and the tobacco pipe was not only a companion in daily life, but often entered their work as well.

Just think of Tolkien, who made it a recurring element in the world of The Lord of the Rings, or Einstein, who considered the tobacco pipe a valuable tool for fostering reflection and inner calm.

The tobacco pipe today: does it continue to be a symbol of reflection?

In an increasingly frenetic world dominated by the logic of disposability, the tobacco pipe stands out as a symbol of rupture and resistance.

Its strength lies precisely in the active participation it requires from the smoker and in the time it takes to perform its ritual of slow and precise gestures.

Today, the tobacco pipe has become a symbol of reflection and refuge: a personal space in which to retreat without escaping, but to find calm, order and meaning, in a ritual that comforts and protects those who feel overwhelmed by the violence and insecurity of the modern world.

Why the tobacco pipe still has appeal and meaning in the modern world

Today the tobacco pipe is experiencing a new positive trend, driven by the rediscovery of the pleasure of tasting and the growing passion for collecting.

A phenomenon fueled by the huge variety of models available today, much richer than in the past, thanks to the creative flair of contemporary craftsmen.

Attention to detail has reached such levels that some tobacco pipes are true collector's items, capable of attracting not only experienced smokers but also those looking for a unique design piece that combines aesthetics and smoking pleasure.